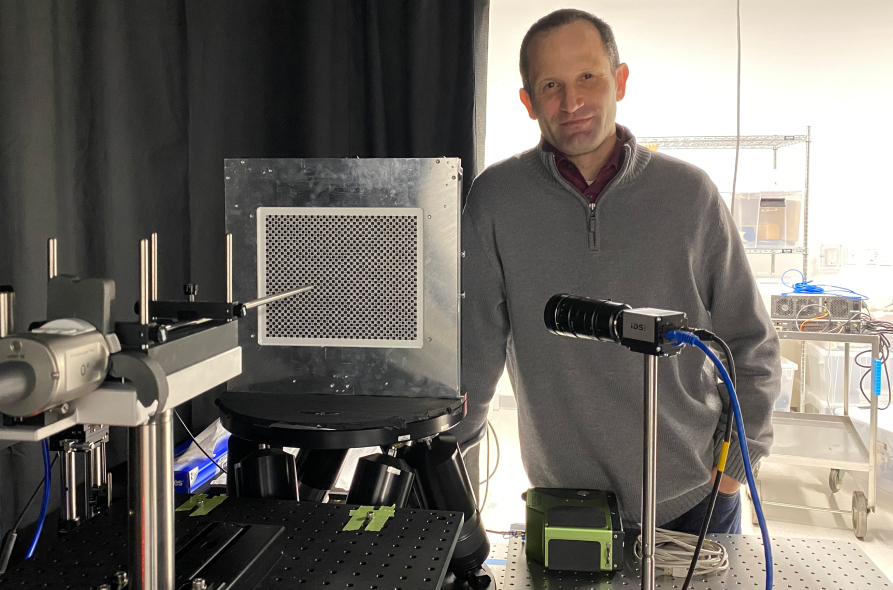

When he was getting a Ph.D. in electrical engineering at Stanford University, Jeffrey DiCarlo became fascinated by a question that might not seem all that relevant to electrical engineering: how do we perceive the world visually? When you think about it though, this subject is actually quite pertinent. After all, visual perception—how the eye and brain grasp and process reality—occurs via electrical signals traveling through the nervous system. DiCarlo began working with a psychology professor who also taught electrical engineering, focusing on how humans discern color and texture.

He is still fascinated by this topic; in fact, he’s spent the past two decades thinking about visual perception. He’s put his fascination to practical use. For the past 12 years, he’s worked at Intuitive, helping to develop better ways for surgeons to see what they need to see when they’re using the company’s robotic surgical systems.

For any surgeon, being able to see clearly during a procedure is crucial. This is perhaps especially true for minimally invasive surgery, where the clinician is looking at a monitor, rather than directly at the patient’s anatomy. Since its inception, Intuitive has focused on giving surgeons a bright, well-defined view of the tissue they’re operating on. As the company has grown, and its products have evolved, this emphasis has only increased; there are now more than 100 people working on the vision technology for the company’s various robotic systems.

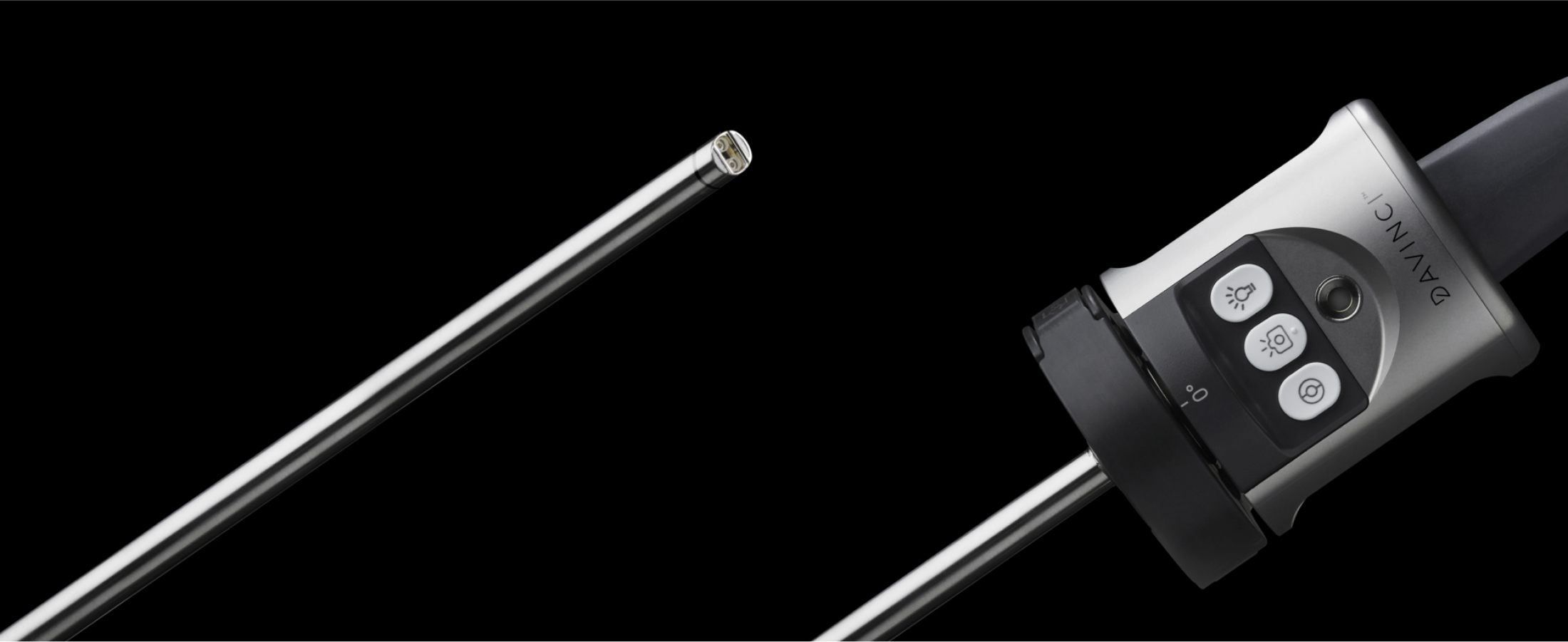

Over the past quarter-century, Intuitive has added key innovations to its vision technology. The company’s first vision system included three-dimensional vision, so that surgeons could see tissue in a more realistic way. After a few years, Intuitive added HD. More recently Intuitive engineers have reduced the size of the camera, so that it can fit onto the tip of the endoscope—so-called chip-on-tip technology. This reduces the size of the endoscope, without lowering the quality, which can reduce the size of the incision. It can also help give surgeons increased maneuverability and control during procedures. The system has also steadily improved the subtlety with which it presents the colors, tones and textures of patients’ tissue—crucial information for surgeons.

“Intuitive has made a real investment in image quality,” says DiCarlo, who is Intuitive’s vice president of advanced imaging. “That’s something that surgeons really care about.”

DiCarlo says Intuitive’s vision system is much more than simply a camera. “It really involves so much more than that,” he says. “There’s the light source; how can we optimize that, so the camera picks up the information it needs? There’s the image processing; how do we integrate the raw information from the lenses and sensors so that it’s as accurate as possible? Then there’s the display; how do we present the images so the surgeon has the clearest, sharpest view?”

As this suggests, the work requires input from many different kinds of experts, including electrical and mechanical engineers, software engineers and industrial designers. “At Intuitive, everybody knows that no one person can solve the problem,” DiCarlo says. “Everybody works together to find the best solution. That’s the part that I really enjoy, the part that I look forward to every day.”

These experts must find solutions that solve for a range of constraints. Because robotic surgery is minimally invasive, the vision system must be extremely compact. For example, the lenses on the tip of the endoscope—there are two, one for each eye, so the surgeon can have three-dimensional binocular vision—are each less than four millimeters in diameter, allowing them to fit into an eight-millimeter endoscope. Three millimeters is roughly the size of a tiny screw. Intuitive’s latest endoscope system, introduced in 2019, has another advantage: it keeps more of the visual field in focus. All tissue that lies between two and 14 centimeters from the lens is sharp, ending the need for surgeons to constantly refocus the camera lens. The company also manufactures its own endoscopes, which helps create a seamless system.

Space isn’t the only limiting factor: there’s also time. Every image must travel what Intuitive engineers call the “imaging pipeline”—the sequence of steps that span from image acquisition to final display. Between the light hitting the camera sensor and the surgeon seeing the scene in the viewfinder, the image must go through more than ten separate steps. To ensure that the surgeon sees exactly what’s happening as it happens, the image is refreshed 60 times a second.

“That gives us 16 milliseconds to get the image adjusted before the surgeon sees it,” DiCarlo says. “That’s the limit, because there’s another frame coming down the line.”

Among the tasks that the vision system has to accomplish in this tiny time frame:

DiCarlo likens the design process to playing Whac-A-Mole. “If you spend all your time getting one thing perfect, a completely different issue crops up—one that was masked by the first thing you fixed. It’s really important to stay focused on the big picture, which is what the surgeon needs to see during surgery.”

To better understand what to focus on, DiCarlo and his colleagues rely heavily on surgeons for input and advice. Often, he says, what surgeons want from the image is different from what he and his colleagues expect. Not long ago, he was talking to a surgeon, who said that a new endoscope image looked “digital.” At first, DiCarlo was confused by this—after all, Intuitive’s vision systems have always been digital. But then the surgeon invited him to watch a procedure so he could see for himself. In that setting, DiCarlo understood what the surgeon was referring to. Because they are making alterations to patients’ tissue, surgeons tend to focus on the area at the center of the image, the tip of the needle.

“What we realized,” DiCarlo says, “is that a lot of the time, that’s where the surgeon is looking—where to put the tip of the needle. So that part of the image has to be especially clear.” DiCarlo and his colleagues modified the system, eliminating the issue.

DiCarlo says many surgeons are interested in technologies to help them see more than the human eye typically does. “We want to give the surgeon new visual information,” he says. Some Intuitive systems already offer Firefly, a technology that uses near-infrared fluorescence for real-time visualization of blood vessels, lymphatic vessels and other often-hard-to-see tissue. DiCarlo and his colleagues are working to develop new imaging technologies that will further enhance a surgeon’s understanding and view, beyond what the naked eye can see.

As challenging as his job can be, DiCarlo loves it. “There’s a ton of brainstorming,” he says. “A ton of ‘hey, can we improve this? Can we improve that?’ There’s always a solution. And it’s important work. I mean, we’re helping patients, helping doctors help patients. To me that’s very fulfilling.”

Important safety information

For important safety information, please refer to www.intuitive.com/safety. For a product’s intended use and/or indications for use, risks, full cautions, and warnings, please refer to the associated User Manual(s).